Welcome back to Reading the Weird, in which we get girl cooties all over weird fiction, cosmic horror, and Lovecraftiana—from its historical roots through its most recent branches.

This week, we’re starting on Shirley Jackson’s The Haunting of Hill House, first published in 1959. Today we’re covering Chapter 1, Parts 1 and 2. Spoilers ahead.

The opening paragraph, in necessary full:

“No live organism can continue for long to exist sanely under conditions of absolute reality; even larks and katydids are supposed, by some, to dream. Hill House, not sane, stood by itself against its hills, holding darkness within; it had stood so for eighty years and might stand for eighty more. Within, walls continued upright, bricks met neatly, floors were firm, and doors were sensibly shut; silence lay steadily against the wood and stone of Hill House, and whatever walked there walked alone.”

Dr. John Montague took his degree in anthropology. That field comes closest to legitimizing his true interest, the analysis of supernatural manifestations. Determined to publish a “definitive work on the causes and effects of psychic disturbances in a house commonly known as ‘haunted,’” he’s set his sights on Hill House.

After long and costly negotiations with the current owners, he’s succeeded in renting the place for three summer months. In the nineteenth-century heyday of ghost-hunting, an investigator might have easily filled a spectral mansion with fellow enthusiasts; Montague has to hunt for assistants.

He combs the records of psychic societies, sensational newspapers and parapsychologists to assemble a list of people who’ve been involved, however briefly, in “abnormal events.” Having culled out the dead, the “subnormally intelligent,” and the attention-hungry, he’s found a dozen names. He sends letters inviting the twelve to summer at an old but comfortable country house and aid in the investigation of “various unsavory stories” circulated about the place. Of the four who reply, only two actually show up.

Buy the Book

The Fourth Island

Eleanor Vance, thirty-two, has spent the last eleven years nursing her invalid mother. Through all the drudgery and isolation, the “small guilts and small reproaches, constant weariness, and unending despair,” she has “held fast to the belief that someday something would happen.” What happens is her mother’s death and a comfortless residence with older sister Carrie and Carrie’s husband and daughter.

What’s in Eleanor’s past to interest Montague? When Eleanor was twelve and her father a month dead, stones rained for three days inside and outside the Vance house, while sightseers gathered to gawp. Mrs. Vance blamed the neighbors. Eleanor and Carrie secretly blamed each other. The rocky deluge ended as mysteriously as it began, and eventually Eleanor forgot about it.

Though her husband verifies Montague’s academic credentials, Carrie suspects Montague wants to use Eleanor for—experiments, you know, the way doctors do. Or else he intends to introduce her to “savage rites” unsuitable for unmarried women. Eleanor herself has no qualms. She jumps at the doctor’s invitation, but then, she “would have gone anywhere.”

Theodora—the only name she uses—is not at all like Eleanor. She believes duty and conscience are “attributes which belonged properly to Girl Scouts.” She owns a shop and lives in “a world…of delight and soft colors.” She also lives with an apartment-mate of unstated gender and romantic affiliation. Dr. Montague selected her because of a parapsychological experiment in which she was able to name nineteen cards out of the twenty held out of her sight. Montague’s invitation entertains her, but she intends to decline it until on a whim she changes her mind and plunges into an argument with her “friend” that will require an extended separation to restore peace. She leaves for Hill House the next day.

One more person, unconnected to any “abnormal events,” joins Montague’s party. Mrs. Sanderson, the homeowner of Hill House, has decided a family member should supervise Montague. Her nephew Luke has, she despairs, “the best education, the best clothes, the best taste, and the worst companions” of anyone she knows. He is also a liar and thief, though unlikely to pilfer the house’s silver—as selling it would take too strenuous an effort. Montague welcomes Luke; he perceives in him “a kind of strength, or catlike instinct for self-preservation” that may prove invaluable.

In fact, Luke has always confined his dishonesty to “borrowing” petty cash from his aunt’s pocketbook and cheating at cards. Someday he’ll inherit Hill House, but he never expected to live there. Nevertheless, the idea of “chaperoning” Montague’s party amuses him.

The party is made up. The forces are gathering. Hill House awaits, holding darkness within.

Anne’s Commentary

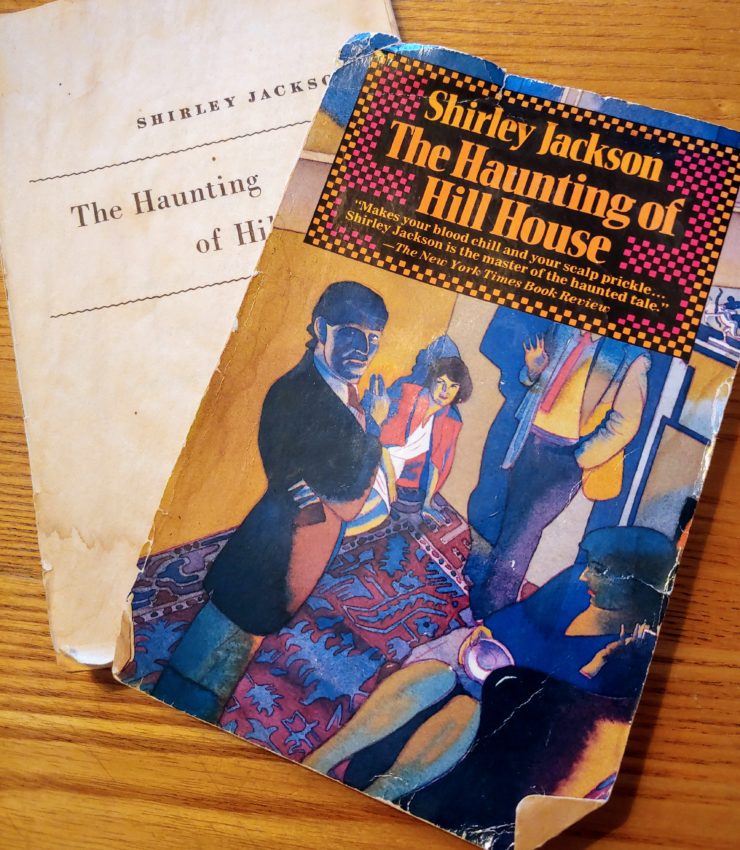

Here’s my first copy of Hill House, published by Penguin in 1984.

I purchased it the same year, and it is proof of my continuing devotion to Jackson’s masterpiece. For her greatest novel, some champion The Sundial, which preceded Hill House, others We Have Always Lived in the Castle, which followed. Both brilliant works, but no, I must contend it’s Hill House for the win, every day and always. It was every day for years that I read at least a few pages, for that first copy graced the tank-top of our downstairs toilet, its pages slowly yellowing and acquiring water-blotches, its cover gradually losing its grip on the spine until, detached, it began a second life as a bookmark.

Penguin 1984 is my pick of the many covers Hill House has worn since its publication in 1959. The illustration’s overhead perspective (who or what is looking down at our intrepid ghost-hunters?) and subtly skewed angles (like all of Hill House’s) create instant viewer unease. Each ghost hunter is captured in a telling pose. Dr. Montague pauses mid-lecture to glance with wary curiosity ceilingwards. Luke (rendered inexcusably headless by the title block!) still manages to convey a charming self-centeredness lounging against the mantelpiece. Theodora reposes with feline grace, shapely legs thrown over her chair’s arm, cigarette dangling from one hand, empty teacup from another. And Eleanor! There she huddles on the carpet, in a (skewed) corner, peering up at Montague with brows-drawn concentration. Or apprehension? Or suppressed anger that could manifest as stranger things in this utterly strange—and malignant— house?

I think Lovecraft would have adored Hill House. Stephen King certainly does. In Danse Macabre, his critical survey of supernatural fiction and film, he described its opening paragraph as “the sort of quiet epiphany every writer hopes for: words that somehow transcend the sum of the parts.” Yes, that. Jackson’s opening is simultaneously spare and lush, controlled and lyrical. It is redolent of the “garlic in fiction” Jackson described in a lecture shortly after completing Hill House. By “garlic,” she meant images or symbols that, if used too heavily, overpower the “story-dish”; judiciously introduced, they render it delicious. The abstraction of the opening’s first clause is spiced up by the second clause, in which it’s not any old live organisms that dream, but larks and katydids. Larks! Katydids! Why these specific creatures? Why the swoop from the soaring and ecstatic bird beloved by romantic poets to a mundane insect with so folksy an onomatopoeic name? The particularity and whimsy of the pair tempers the preceding solemnity, making us smile before we are chilled by learning that Hill House is not sane.

Does this mean Hill House doesn’t dream, a living thing driven to madness by the absolute reality in which it exists? We’re compelled to wonder what constitutes absolute reality. Can it be so very bad when Hill House is so reassuringly sturdy? More garlic in fiction: Jackson doesn’t tell us the building’s in good repair. She tells us walls continue upright, bricks meet neatly, floors are firm, doors are sensibly shut. Why worry? I’ll tell you why. For all this normality, Hill House holds darkness within, and silence lies steadily upon it, and most of all, whatever walks there walks alone.

Do you really want to rent this place? Dr. John Montague does. Of course he does: He’s an academic with an academically-legitimate interest in the occult who’d fit comfortably in any number of weird tales. He’s the character we can trust to keep his head when uncanny shit starts happening, because he’s studied him some uncanny shit. Also he can temper his intense curiosity with caution. Look how carefully he selects his co-investigators, weeding out the kooks and phonies. Surely he’s chosen the right people.

Right?

Eleanor seems so unassuming, despite that telekinetic or poltergeistly stone-fall associated with her. Surely she’ll be grateful enough for an invitation anywhere to cause no trouble.

Theodora’s scientifically proven telepathic abilities could prove useful, and her empathy should make her a team player. Don’t blame Montague for not taking her need to be the center of attention into account. All he knows about her are her card-reading scores.

For a reader in the late 1950s, Theodora’s ambiguous live-in “friend” would also be of concern. As Tricia Lootens points out in her article “Whose Hand Was I Holding,” early drafts of Hill House made it explicit that Theodora’s a lesbian. In Shirley Jackson: A Rather Haunted Life, Ruth Franklin writes that her subject’s history of “crushes” on women notwithstanding, “Jackson—typically for her era and her class—evinced a personal horror of lesbianism.” Jackson was upset when her Hangsaman (1951) was described as “an eerie novel about lesbians.” Yet she admitted she wanted to create a “sense of illicit excitement” between protagonist Natalie and the ambiguously named but female Tony. Oh, but Tony was neither male nor female, being just a “demon in [Natalie’s] mind.” I suppose Jackson wanted to avoid having Hill House labelled an “eerie lesbian novel,” so she left Theodora’s orientation rather convolutedly unstated while still infusing Theo and Nell’s relationship with a certain “illicit excitement.”

What to expect from Luke, mildish bad-boy that he is? Given how he heartlessly flirts gifts out of Mrs. Sanderson’s female friends, he could turn the Theodora-Eleanor thing into a triangle, equally heartlessly. Theodora, we assume, wouldn’t take his flirting seriously. Eleanor, however, could make Luke that “something” that must happen to her “someday.”

As epigraph to her chapter on Hill House, Ruth Franklin quotes from unpublished notes Jackson wrote in 1960. In part, the epigraph reads: “then it is fear itself, fear of self that I am writing about…fear and guilt and their destruction of identity…why am i so afraid?”

Those authorial musings may be something to remember as we read on.

Ruthanna’s Commentary

Unlike Anne, I don’t know Jackson’s work nearly as well as I’d like. Before starting this column, I’d read nothing of hers except for “The Lottery.” So I’m arriving at Hill House as a newcomer, invited with only minimal explanation of the strangeness expected within. I’m looking forward to it, and bracing myself.

Two sections in, I’m in love with the narrative voice. I would honestly be happy with an entire book of closely observed, dryly snark-ful biographical sketches. I would be even happier to summon Jackson’s ghost for that most modern of pastimes: exploring weird and overpriced home listings on real estate sites. Hill House itself is at least as compelling as the human characters; what tales would she spin from the colonial with the historical jail in the basement, or the set of charming cabin photos in which Bigfoot suddenly appears on the porch?

About that opening: what does it mean for a living organism to exist under conditions of absolute reality? It’s a question that brings us back to the core idea of cosmic horror. If sanity cannot consist of accurately representing the world, perhaps it requires representing the world in such as way that one can detect patterns and act on them, even if that involves filtering out a vast influx of the incomprehensible and overwhelming. Or perhaps—if even the little dreams of larks are sufficient respite—it simply consists of being able to imagine other possibilities. Futures and pasts, just-missed alternatives and wild speculation, escape fantasies and distillations of our most vital passions into embodied metaphor—maybe we can only bear reality if cushioned by these bulwarks of possibility.

Any of these interpretations makes Hill House instantly terrifying. Is it a place where the things we deny force themselves into our consciousness? Or a trap that doesn’t allow its captives to imagine the way out? Perhaps both: expanding awareness and limiting options all at once. (Also, catch that in-passing implication that Hill House is a “live organism.” Brrr.)

Getting back to the humans, I instantly sense a familiar pattern: the small ensemble perfectly designed to cause each other at least as much trouble as their setting. No Exit, for example—are hauntings also other people?

Montague draws the driest judgment from our narrator. He’s “scrupulous about his title,” something that most PhDs get over a couple of weeks after defending their dissertations, and eager for the respect that his work itself is unlikely to earn. He “thought of himself as careful and conscientious”—this is very different, of course, from being careful and conscientious. He crosses off potential assistants who might grab “the center of the stage,” presumably because they’d grab it from him. Fun guy to spend the summer with.

Then we have Eleanor: sheltered, unhappy, perhaps a bit spiteful. (Though it sounds like she comes by it honestly.) After a life of taking care of others, with little to show for it, she’s “held fast to the belief that someday something would happen.” I am all sympathy—she seems ripe for “something” to throw her a life raft and pull her up into the fresh air of character development. I can’t blame her for being willing to go anywhere in search of that change. Not to mention, willing to go away from her sister and brother-in-law, who are deeply worried that such development might involve experiments.

I’m kinda hoping—though not expecting on the page—that those experiments will involve Theodora, who appears about as overtly queer as would have been permitted when this book came out. After all, she’s just had a violent quarrel with her “friend” that she lives with, and who carves sculptures of her, and who she gives books by authors who also (probably, anonymously) write lesbian erotica. With “loving, teasing” inscriptions, yet. [ETA: I absolutely read the “friend” as female, though looking back I see that there are in fact no pronouns. I stand by my interpretation, based primarily on the Alfred de Musset, and see from Anne’s comments that I’m not completely off-base.]

I’m less enamored of Luke, but I suspect that’s intentional. Presumably he’s there to cause trouble, and I expect he’ll get that accomplished handily. He seems poorly suited to handle a haunting. Then again, there’s that “cat-like instinct for self-preservation,” so I could be wrong.

This week’s metrics:

The Degenerate Dutch: Jackson is exquisitely aware of the ways in which the pressures and unfairnesses of the world shape people. Eleanor in particular seems to have suffered from the expectations of care often placed on women, and the sort of artificial enforced innocence that goes along with it.

Weirdbuilding: Building on a long Gothic tradition of supernaturally iffy architecture, Hill House lays the foundation for most modern haunted house novels.

Madness Takes Its Toll: “No live organism can continue for long to exist sanely under conditions of absolute reality.” Hill House, alas for visitors, has long since correlated its contents.

Next week, we can’t resist finding out what the author of Little Women does with the weird, and have picked Louisa May Alcott’s “Lost in a Pyramid, or the Mummy’s Curse” from the contents of Weird Women. You can also find it on Project Gutenberg. Hmm, where have we read about someone lost in a pyramid before….

Ruthanna Emrys is the author of the Innsmouth Legacy series, including Winter Tide and Deep Roots. Her short story collection, Imperfect Commentaries, is now available from Lethe Press. You can find some of her fiction, weird and otherwise, on Tor.com, most recently “The Word of Flesh and Soul.” Ruthanna is online on Twitter and Patreon, and offline in a mysterious manor house with her large, chaotic household—mostly mammalian—outside Washington DC.

Anne M. Pillsworth’s short story “The Madonna of the Abattoir” appears on Tor.com. Her young adult Mythos novel, Summoned, is available from Tor Teen along with sequel Fathomless. She lives in Edgewood, a Victorian trolley car suburb of Providence, Rhode Island, uncomfortably near Joseph Curwen’s underground laboratory.